The first product liability case against Johnson & Johnson and its medical device division, DePuy Orthopaedics, involving the DePuy ASR metal-on-metal hip implant began on January 25 in Los Angeles. Led by Michael Kelly, attorneys for the plaintiff, Loren Kransky, seem to be off to a strong start, hammering home the point that DePuy knew its ASR hip implant had design defects, and concealed them from physicians.

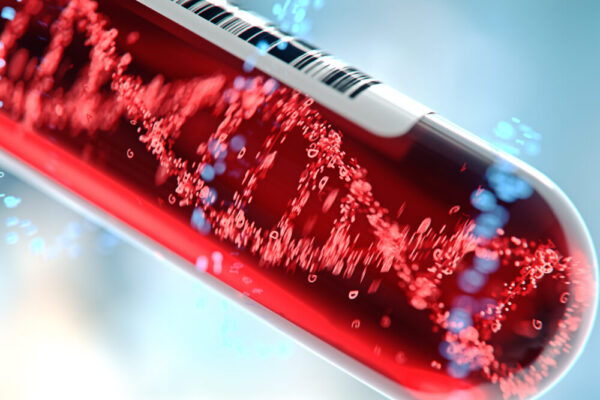

Kransky’s lawyers claim the implanted metal cups did not stimulate ingrowth of surrounding bone, making them unstable in the hip. They also claim that increased wear created from the shallow design of the ASR cups, in which a metal ball atop the femur rotates, led to toxic debris of cobalt and chromium ions being deposited into patients' bloodstream. In his opening statement, Mr. Kelly quoted from an internal DePuy document dated September 27, 2007, which described how "massively increased wear" can occur when the cup is "oriented at a steep angle." In a May 2, 2008 e-mail, DePuy's head of U.S. marketing, Paul Berman, acknowleged, "We will ultimately need a cup redesign but the short-term action is to manage perceptions." Those marketing guys are always a great source for stupid statements.

The first witness called by the plaintiff was Magnus Fleet, a DePuy project manager who joined the company to work on the ASR design after spending 15 years working on automotive brake systems. There was no one with medical device experience available? Mr. Fleet testifed that his design team conducted a failure mode and effect analysis of the shallower ASR cup design, and forecast that this design would lead to minimum boney ingrowth. Again, boney ingrowth is necessary for the long-term stability of the implant.

DePuy advised surgeons that the ideal angle at which to implant the ASR cup was 45 degrees. However, a study showed that more than half the ASR devices were implanted at greater angles. Indeed, even the surgeon who helped DePuy design the device experienced difficulty implanting it into his patients at a 45 degree angle. This is important because Mr. Fleet also testified that DePuy had data indicating that angles above 55 degrees resulted in increased cobalt and chromium ion deposition into the bloodstream.

On July 2, 2008, Paul Berman authored an e-mail about DePuy sales representatives "telling surgeons DePuy is making an emergency change to the ASR cup. We must keep the ASR 2 project under total wrap, particularly in the U.S. where we will not make the change immediately." "Lastly, I propose any future reference to ASR 2 is Project Alpha."

In his testimony, Mr. Fleet said DePuy scrapped efforts to redesign the cup, and that surgeons were never told that the ASR failed and required follow up revision surgeries at a rate that was eight times that of the DePuy Pinnacle hip device. Instead of worrying so much about managing perceptions and creating code names for the redesign project to fix its unreasonably dangerous product, DePuy should have heeded its early studies and not gone to market with this flawed design. Failing to do that, DePuy should have proceeded with Project Alpha and made the design safer. DePuy did neither.

At trial, DePuy is taking the standard approach of pointing the finger elsewhere. Its attorneys say that Mr. Kransky's elevated metal levels in his body are not from the DePuy ASR, a device known to shed toxic cobalt and chromium ions, but rather from smoking or being exposed to Agent Orange in Vietnam. Blah blah blah. This finger pointing, of course, does not address the fact many plaintiffs had to undergo revision surgery to remove these defective implants, causing further damage to the hip structure.

Comments for this article are closed.